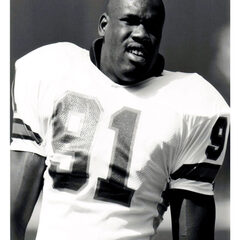

Denver's Ron Lyle, the son of a preacher father and missionary mother who brawled with the best during a golden age of boxing heavyweights, died Saturday morning. He was 70.

With Muhammad Ali, George Foreman, Joe Frazier and others, Lyle was part of a string of boxers who dominated the sport in the 1970s. They faced off in a series of classic fights, back when boxing was broadcast on radio and network television.

"Ron was a good-hearted guy. But he could fight like hell," said Earnie Shavers, a hard-hitting fellow heavyweight who fought Lyle in 1975. "He was tough. He could take a good punch."

Lyle entered a Denver hospital Nov. 18 with stomach pains and died eight days later after a stomach abscess became septic, said Sharon Dempsey, his sister.

The former contender is on the short list of the greatest boxers in Colorado history, along with "Manassa Mauler" Jack Dempsey and Denver's Sonny Liston.

Lyle's tenure in the ring, though, started later in life — and was part of a decades-long shot at redemption.

One of 19 brothers and sisters, Lyle grew up in a strict God-fearing family in northeast Denver. But at 19, after dropping out of Manual High School, Lyle was convicted of second-degree murder in the shooting death of 21-year-old gang rival Douglas Byrd. Lyle argued he was being attacked with a lead pipe and was not the one who pulled the trigger.

"We were all in it together. I was involved," Lyle told The Denver Post, saying he could have received a softer sentence if he had revealed the killer. "But where do you live after that?"

He served 7 1/2 years in a Cañon City prison and nearly died on the operating table after being stabbed by an inmate.

A standout basketball player as a teen, Lyle learned to box in prison, where Denver cable-TV magnate Bill Daniels noticed his standout talent. Daniels asked Gov. John Love to pardon Lyle, then took Lyle under his wing on a city boxing

After winning a national amateur title, Lyle turned professional at 29 — a late start for prize fighters. But he won his debut bout at the Auditorium Arena in Denver in 1971.

It was the first step in what Lyle hoped would be his atonement, especially in the eyes of his very religious parents.

"(My mother) died a saint. The things I did broke her heart," Lyle told The Post in 1994. "When I was in prison, my mother traveled in the snow to see me. So I decided I would do something to make her proud. I decided to become heavyweight champion of the world."

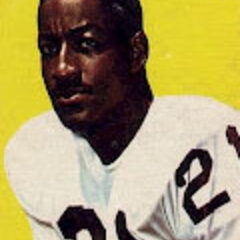

Lyle in the mid-1970s took part in a grand trio of fights that pitted him against the best in the boxing business.

He fought Muhammad Ali in Las Vegas in May 1975 for the heavyweight title, during Ali's second reign as champion. Lyle, a heavy underdog, was well ahead of Ali on scorecards through 10 rounds, as Ali played rope-a-dope, letting Lyle lunge at him with punches. But Ali let loose with combinations in the 11th, and the referee stopped the fight, giving Ali a TKO — a technical knockout.

Four months later, Lyle got the better of Shavers in Denver, rallying from a second-round knockdown to knock out Shavers in the sixth.

Then, in January 1976, Lyle fought George Foreman in a classic slugfest. In the fourth round, Lyle and Foreman traded huge punches. Lyle stunned Foreman with a knockdown, but Foreman stood up to put Lyle to the canvas twice. When it seemed as if Foreman was near a TKO victory, Lyle came back to knock down Foreman, face first. Foreman barely got up, then staggered to his corner.

Howard Cosell, who called the fight for ABC's "Wide World of Sports," yelled: "It's not artistic, but it is slugging!" Foreman in the fifth was falling forward onto Lyle, but he pushed Lyle into the corner and KO'd him late in the round.

In 1978, Lyle killed a man, a fellow former inmate who was in Lyle's home. It was ruled self-defense, and he was found not guilty.

Lyle retired in 1980, then attempted a comeback in 1995, winning four fights. He stopped soon after with a career record of 43-7-1, with 31 KOs.

In recent years, Lyle coached kids in the Cox-Lyle boxing program at the Salvation Army Red Shield Center in the Whittier-Five Points neighborhood, near where he grew up. In March, he was elected to the Colorado Golden Gloves Hall of Fame.

Lyle's brother Kenneth said his younger brother loved his family and his neighborhood. "He was the toughest guy in the neighborhood. He would never pick a fight, but he always defended the underdog."

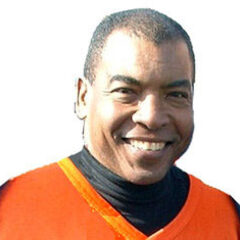

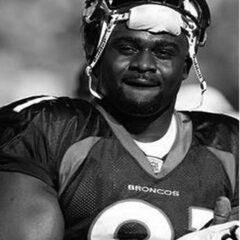

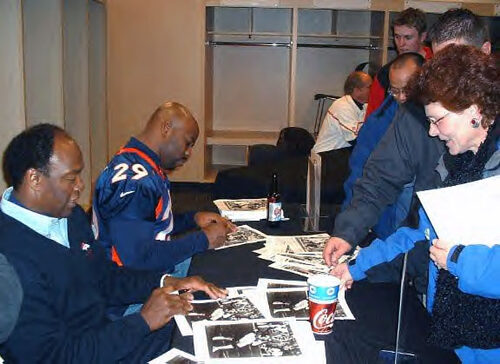

Ron Lyle tending bar at the Purple Martini for Pro Players Association's Celebrity Bartender Night in 2007.

It was Lyle's dream to train heavyweight champions, his sister said Saturday. And for a short time, he helped coach a young Victor Ortiz in Denver, before Ortiz went on to win and lose the welterweight title this year.

"He lived out all his dreams. He trained young kids to feel good about themselves," Sharon Dempsey said. "He loved boxing. That was his heart, his passion. He proved that you can pick yourself up, no matter how far you fall."

Lyle remained part of a small brotherhood of former heavyweights, bonded by their bruises: Ali, Foreman, Frazier, Shavers, Larry Holmes, Ken Norton, Jerry Quarry, Leon Spinks, Jimmy Ellis — and Lyle.

"Fighters are the same," Lyle said earlier this month, after Joe Frazier's death at 67. "It's who we are."

Lyle and Shavers talked on the phone every few weeks, and they often crossed paths with their former rivals.

"In our hearts, we each knew we were the best," Shavers said. "So we didn't argue it. We just knew we fought in the golden era.

http://blog.denverbroncos.com/mark_cooper/

http://blog.denverbroncos.com/mark_cooper/